As a scholar working on the Chinese in Britain, I was excited to embark on BICC’s knowledge exchange partnership with Penguin Books China, researching Penguin’s UK back catalogue of works on China and China-related themes from 1930s to the 1960s. These Penguin first editions encompass an extraordinary array of novels, poetry, reportage and non-fiction for adults and children, from Pearl Buck’s classic The Good Earth (1960) to the notorious Sax Rohmer’s The Mystery of Fu Manchu (1938) and lesser known works of forgotten writers such as Winifred Galbraith and Tsui Chi.

As a scholar working on the Chinese in Britain, I was excited to embark on BICC’s knowledge exchange partnership with Penguin Books China, researching Penguin’s UK back catalogue of works on China and China-related themes from 1930s to the 1960s. These Penguin first editions encompass an extraordinary array of novels, poetry, reportage and non-fiction for adults and children, from Pearl Buck’s classic The Good Earth (1960) to the notorious Sax Rohmer’s The Mystery of Fu Manchu (1938) and lesser known works of forgotten writers such as Winifred Galbraith and Tsui Chi.

Thanks to the Penguin Archive at Bristol University, I was able to unearth the genesis of Penguin’s acquisition of the books and piece together its role in sustaining and shaping knowledge of China in Britain during these decades. My own research has focused on constructions and contestations of Chineseness by examining how migrant Chinese artists, whose lives spanned Britain, Italy, South Africa, China and Taiwan from the 1930s to the present day, negotiate identity and belonging in diaspora.

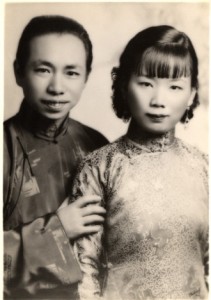

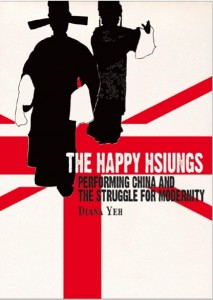

Of particular relevance to the Penguin project is the world of Shih-I and Dymia Hsiung, two once highly visible, but now largely forgotten Chinese writers in Britain. Shih-I rose to worldwide fame with his play Lady Precious Stream in the 1930s and became known as the first Chinese director to work in the West End and on Broadway. In 1952, Dymia became the first Chinese woman in Britain to publish in English a fictional autobiography, Flowering Exile. In The Happy Hsiungs: Performing China and the Struggle for Modernity (Hong Kong University Press, 2014), I recover the Hsiungs’ lost histories and discuss the challenges they faced in representing China to the rest of the world and becoming accepted as modern subjects, at a time when knowledge of China and the Chinese was persistently framed by colonial legacies and Orientalist discourses.

While my analysis focused on how the Hsiungs’ success was shaped by unfolding socio-economic, cultural and political circumstances, the Penguin project allows me to locate their works in a literary context. Ernest Bramah’s series of Kai Lung stories (1936–38) and China muckraker Samuel Merwin’s fantastical tale of China, Silk (1942), highlight the popularity of chinoiserie that helped propel Hsiung to fame. It was also interesting to compare Hsiung’s limited success with his play The Professor of Peking (1939), which focused on the political realities of China during the warlord period to American Pulitzer-prize-winning journalist Edgar Mowrer’s Mowrer in China (1938), a report of the unfolding war in China, published as a Penguin Special.

In the Happy Hsiungs, I detail how Dymia Hsiung’s Flowering Exile, a story of her family’s life in Britain from the late 1930s to the early 1950s, was criticized by the press at the time as ‘prosaic’ when compared to other contemporary tales of a ‘China of legend’ that captured ‘the strangeness and the charm of that fabled land’. Yet, if Penguin’s output is anything to judge by, stories of journeys in the opposite direction, from Britain to China, remained popular. While Ann Bridge’s Peking Picnic (1938) and The Ginger Griffin (1951) are both set in the foreign legations in Beijing, Denton Welch’s autobiographical Maiden Voyage (1954) charts his escape from school in England to Shanghai where he was born. Meanwhile, Harold Acton’s Peonies and Ponies (1950), a satire of the foreign community in republican-era Peking, has recently been described by contemporary Penguin author Paul French as ‘the wittiest and best observed novel of the period, and the one that best encapsulates the goldfish bowl world of the privileged’ in China.

In the Happy Hsiungs, I detail how Dymia Hsiung’s Flowering Exile, a story of her family’s life in Britain from the late 1930s to the early 1950s, was criticized by the press at the time as ‘prosaic’ when compared to other contemporary tales of a ‘China of legend’ that captured ‘the strangeness and the charm of that fabled land’. Yet, if Penguin’s output is anything to judge by, stories of journeys in the opposite direction, from Britain to China, remained popular. While Ann Bridge’s Peking Picnic (1938) and The Ginger Griffin (1951) are both set in the foreign legations in Beijing, Denton Welch’s autobiographical Maiden Voyage (1954) charts his escape from school in England to Shanghai where he was born. Meanwhile, Harold Acton’s Peonies and Ponies (1950), a satire of the foreign community in republican-era Peking, has recently been described by contemporary Penguin author Paul French as ‘the wittiest and best observed novel of the period, and the one that best encapsulates the goldfish bowl world of the privileged’ in China.

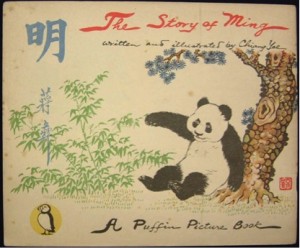

It was also fascinating to explore the works of Chiang Yee and Tsui Chi, who were close friends of the Hsiungs and shared their homes in Hampstead and Oxford. Both wrote for adult audiences and Chiang Yee was popularly acclaimed for his Silent Traveller series, but wrote children’s books for Penguin’s first children’s series – the Puffin Picture Books. While Chiang Yee illustrated his own Lo Cheng: The Boy Who Wouldn′t Keep Still (1942) and The Story of Ming (1944), Tsui Chi collaborated with the illustrator Carolin Jackson for his The Story of China (1945).

It was also fascinating to explore the works of Chiang Yee and Tsui Chi, who were close friends of the Hsiungs and shared their homes in Hampstead and Oxford. Both wrote for adult audiences and Chiang Yee was popularly acclaimed for his Silent Traveller series, but wrote children’s books for Penguin’s first children’s series – the Puffin Picture Books. While Chiang Yee illustrated his own Lo Cheng: The Boy Who Wouldn′t Keep Still (1942) and The Story of Ming (1944), Tsui Chi collaborated with the illustrator Carolin Jackson for his The Story of China (1945).

Other notable highlights of the collection include feminist adventurer Alexandra David-Néel’s My Journey to Lhasa (1940), an account of her extraordinary 2000-mile journey on foot to the forbidden city. Disguised as a beggar and accompanied by a novice monk whom she later adopted, she arrived in Lhasa in 1924, winning her accolades as the third European to reach the city in the twentieth century. Equally remarkable is the life of Winifred Galbraith, a missionary teacher who repeatedly defied orders from the British authorities to leave China during Mao’s attempted Autumn Harvest Uprising. Her book, entitled (not without protestation), The Chinese about ‘the nature of the civilization on which China is building her new society’, was published by Penguin as a Pelican in 1942.

Disputes between Penguin editors, notably in the acquisition of Sax Rohmer’s The Mystery of Fu Manchu (1938) – and negotiations between editors, authors, translators and illustrators – account for and shaped Penguin’s varied output on China and China-related themes during this period. Such contestations in the construction of China and Chineseness, of course, continue today.

In March 2014, supported by BICC, I gave a series of talks in China about the intersections of the Penguin China project with my research on the lives of the Hsiungs, at the Bookworm International Literary Festival in Beijing and Suzhou and at the Royal Asiatic Society Shanghai. I also discussed both projects in the context of my current research on contemporary youth identity formations at the University of Nottingham Ningbo China. As Penguin China approaches its tenth year anniversary, plans are afoot to feature some of these early Penguin writers on China in a forthcoming touring exhibition in Asia. Such projects promise to contribute to the vital task of widening knowledge of and reflecting on British–Chinese relations both historically and in the present day.

Dr Diana Yeh will be taking up a position as Senior Lecturer in Sociology at the University of Winchester in June 2014.